Kapi is the Pitjantjatjara word for water. Pitjantjatjara is the main language spoken by the Anangu, the traditional owners of the Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park.

Rain was the last thing I expected when I booked a week-long working retreat at Uluru, the spiritual heart of Australia.

I had just finished a six month stint in the corporate world in Melbourne as a Technical Writer and needed to refresh before beginning the hard slog of getting my first novel to print. It was early December when the weather averages 40oC in Central Australia and I anticipated spending most of the time in an air-conditioned hotel room – eating, sleeping and working. I packed my camera along with my computer; the only concession to my tourist status.

It was exactly 40oC the day I arrived. The base walk around the rock was closed due to the temperature and the heat was so much more debilitating than 40oC in Melbourne that I could only manage to collect the tourist information, do some shopping and book a pre-dawn tour of the Field of Light installation.

Many tourists were travelling to Uluru simply to see the Field of Light installation, situated just outside the Yulara resort. The vision of English artist Bruce Munro, it consists of a vast expanse of 50,000 solar powered glass bulbs mounted on stems, emulating desert flowers. The bulbs change color and brightness in hypnotic waves of undulating light, and can only be viewed at night.

Although intriguing, the installation felt strangely out of place in the desert environment; a peculiar man-made construction, plonked haphazardly in such vast surrounds. By far the most enthralling sight was dawn over Uluru itself – a stunning vista that needs no artificial fanfare.

I immediately had to get out to the rock and headed back to the resort to organize transport to the National Park. It was 36oC and the base walk was still open, so I wasn’t missing my chance – even though tourists are advised not to attempt it after 11 am in the summer months.

Armed with less water than the recommended amount of one litre per hour, a huge sunhat, Aeroguard and sunscreen, I set off around the perimeter. Constantly stopping to take photos, it took three and a half hours to complete the 9.4 km journey. It was absolutely gruelling in the heat and I probably should have known better, but I couldn’t help myself.

I’d been to Uluru once before, over 25 years earlier, but had been working on a commercial for the Australian Tourism Commission at the time, with little opportunity to enjoy the sights. I’d felt the call to return to Uluru for a couple of years before the stars finally aligned and I was able to make it back.

The work colleagues I’d left behind in Melbourne were surprised to hear I’d booked a week at Uluru, arguing I would only need the standard three days. What would I do with all that time? This sentiment was echoed by the tour guides at Yulara itself, who dubbed me a local as soon as they heard I was staying a full seven days.

A forecast storm arrived the following afternoon and felt like an unwelcome disruption. I hid from its ferocity in my hotel room, like most of the other tourists. All outdoors activities were cancelled, including the evening sessions at the Field of Light installation – which entailed camel rides to the site and fine dining under the stars. It was a devastating development for those tourists who had only scheduled a few days at the Red Centre.

It was still raining the next day when I headed out again, embarking on a second base walk. Uluru looked completely different after the rain. The rusted iron particles in the surface of the rock that are responsible for its fierce orange glow were now streaked black by the runoff from its summit. The landscape was surprisingly lush and the temperature was an enjoyable 30oC.

But what was most astounding was the noise. The water catchment areas were filling up and creatures of all descriptions were finding their voices – especially the frogs. It was a symphony of sounds that immediately called to mind traditional Aboriginal songs and music. I suddenly recognised where those unique sounds emanated from – nature itself. It was a celebration of the coming of water, such a precious commodity for all of life.

Kantju Gorge

In the Central Australian desert, several species of frogs survive drought conditions by burrowing beneath the sand and remaining underground for long periods. In a state of hibernation, the frogs shed their skin several times, creating an impermeable bubble around their bodies to keep the moisture in. After a substantial amount of rain, the frogs reemerge to feed and mate, commencing a rapid breeding cycle where the tadpoles mature in as little as 40 days – before the water dries up again.

The frogs were noisiest at Kantju Gorge and Mutitjulu waterhole, which were now filling with the water pouring off the rock.

It wasn’t until I arrived back at Mutitjulu waterhole in the rain that I recognized I’d found my place of pilgrimage – the reason for the call to Uluru. Honestly speaking, I hadn’t realized I’d been searching for anything. I knew immediately that I would return to the waterhole every day. Not just to check on the changes wrought by the unpredictable weather, but to stay a while and contemplate the wonders of the landscape.

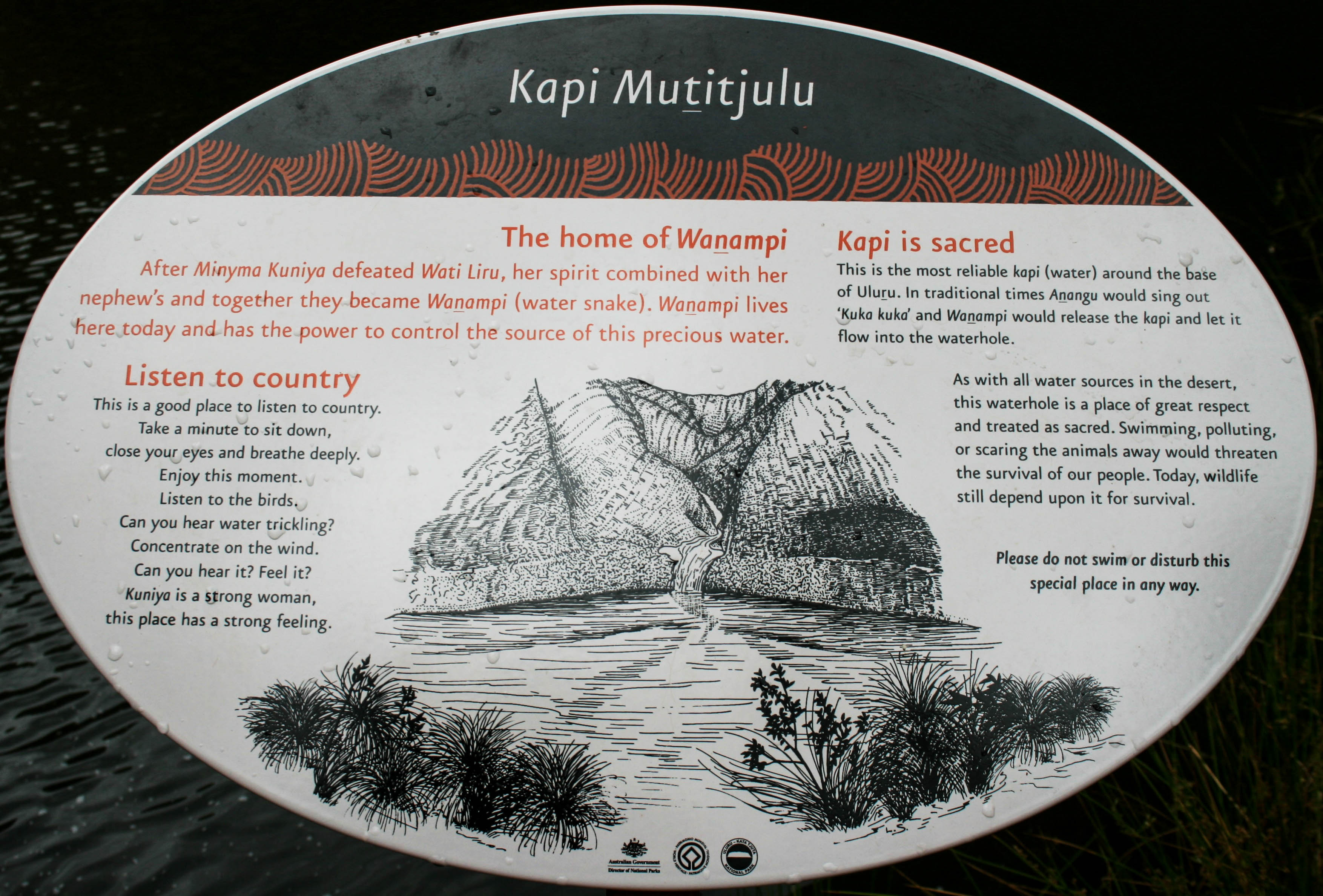

Mutitjulu waterhole is the only perennial water source at Uluru. It is a site of great spiritual significance to the Anangu and especially to women. It is the home of ancestral Wanampi or rainbow snakes. According to the Anangu, if the waterhole becomes empty, the Wanampi bring rain and fill it again. With the rain, the Wanampi go exploring and hunting across the sand dunes.

On my first base walk in 36oC heat, there was little water there – not much more than a puddle. Now the water levels were rising, the frogs were testing their voices, and Mutitjulu waterhole had transformed into a dark oasis in the desert.

I stayed for a couple of hours, just ‘listening to country’. It’s a very different philosophy to the Western focus on exploiting the land for what it might be worth in dollar terms. The every idea that the landscape has something to convey to us and our soul needs this communion is akin to a foreign language to non-indigenous people.

Mutitjulu Waterhole

The rain continued unabated the next day, defying the forecast for clearing conditions. There was talk of a ‘weather event’ at Uluru, so unusual were the circumstances. I returned to Mutitjulu waterhole and stayed the entire day, and it was the most amazing experience. There were few tourists willing to brave the weather, but plenty of locals came to the waterhole.

A woman who was on her way home to Alice Springs, was compelled to call in to check on the waterhole. She said that in the 15 years she had lived at Uluru and the Alice, she had never seen it looking like this.

An Anangu man and his two teenage sons stopped by, all three of them displaying tell-tale crimson paint stains on their skin from the secret corroborees in the area.

Three generations of a local Anangu family arrived together – grandmother, daughter and grandchildren, playfully taking selfies on their smartphones with the waterhole in the background.

Everyone was celebrating the amazing sight that I had by dumb luck simply stumbled across.

Mutitjulu Waterhole

The rock at Mutitjulu waterhole was black by this stage and the water reflected the darkness. It was a stunning sight and the grandmother sat beside me on the seat at the viewing platform, drawing my attention to how the mottled surface of the rock looked like a covering of skin. It was a simple but poignant analogy.

I continued to attend the dawn and dusk viewing sessions at the rock each day, but my focus was always on getting back to Mutitjulu waterhole as quickly as I could. The rain started to clear and the privacy I had enjoyed at the waterhole evaporated with it, as tourists heard word of the amazing spectacle to be seen. Soon busloads of people were crowding onto the viewing platform and disturbing the peace with constant chatter. So much for listening to country.

The surrounding landscape was blossoming and every day seemed to bring new growth. The story behind the Field of Light was that Bruce Munro had been camping at Uluru in 1992 during a period of above average rainfall and his installation had been inspired by the regeneration of the local flora.

Mutitjulu Waterhole

The desert flowers were blooming again in another period of above average rainfall and lit up spectacularly in the sunlight – far more spectacularly than the Field of Light installation, which seemed like a poor imitation of the natural world in comparison.

Surely this is one instance where nature’s beauty cannot be surpassed – so why would you try?

Witnessing this unexpected ‘weather event’ at the rock absolutely felt like a gift. The tour guides advised that only 2% of visitors get to see rain at Uluru – you should get out there and not worry about getting wet, it’s a privilege. And yet, it was nothing compared to what followed two weeks later, when a ‘once-in-50-year’ rainfall event hit Uluru on Christmas Day 2016. Almost an entire year’s rainfall was dumped on the region in a single day and the flooding temporarily closed the Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park.

A message of renewal from the spiritual heart of this ancient continent? What did you hear, if anything?

I may not have achieved anywhere near the amount of work that I’d hoped for during my week away, but I had reconnected to my essential self and this proved more important than anything in the months that followed, getting Redemption to the finishing line.

On the plane home from Uluru, I realized that I didn’t know anything about the indigenous culture in the Western Districts of Victoria where I was living and this was entirely my fault. It was bizarre that I had to travel so far, to the Red Centre of this country, to realize that simple fact.

I intend to go back to Uluru and much sooner next time. Just to listen to country and to wonder.

References:

Uluru Stories. (2010). Queensland: Tanami Press.